Earth’s environment is totally essential for all times on our blue marble, so it’s no marvel astronomers are keen to look into the clouds of exoplanets round different stars. One fashionable far-flung world—TRAPPIST-1c—was so interesting to researchers as a result of it was beforehand regarded as shrouded in a thick layer of carbon dioxide. But new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), nevertheless, have revealed that it’s extra prone to be a barren rock, with no environment in sight.

When astronomers attempt to get a deal with on what number of planets out in area might help life, the primary place to look is a rocky world like Earth, the place the planet has a sturdy floor for biology to take root. “Small planets are abundant in the galaxy,” says Sebastian Zieba, exoplanet researcher on the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and Leiden Observatory and the lead creator of a research revealed in Nature on the brand new TRAPPIST-1c observations. “At least 20 to 50 percent of stars host a planet similar in size to the Earth.” Astronomers nonetheless don’t know a lot about these rocky planets’ atmospheres, or whether or not they have one in any respect. It’s additionally an open query whether or not M dwarf stars, the plentiful form of star TRAPPIST-1c orbits, may destroy these planets’ atmospheres, rendering them uninhabitable.

JWST is shortly altering that actuality. “There is no other observatory right now which can give us precise measurements like these,” Zieba provides—learning infrared gentle is the place the telescope excels. The fingerprints of many molecules necessary for all times present up in these infrared wavelengths, however these are difficult to detect. To make these measurements, JWST must be far past freezing, a meager 7 kelvin (equal to -500°F).

“For many years, scientists have been modeling the atmospheres of these worlds,” says Daria Pidhorodetska, an astronomer on the University of California, Riverside not concerned within the new analysis. “To finally get to see the real data come from JWST feels like a dream come true.”

[Related: A whopping seven Earth-size planets were just found orbiting a nearby star]

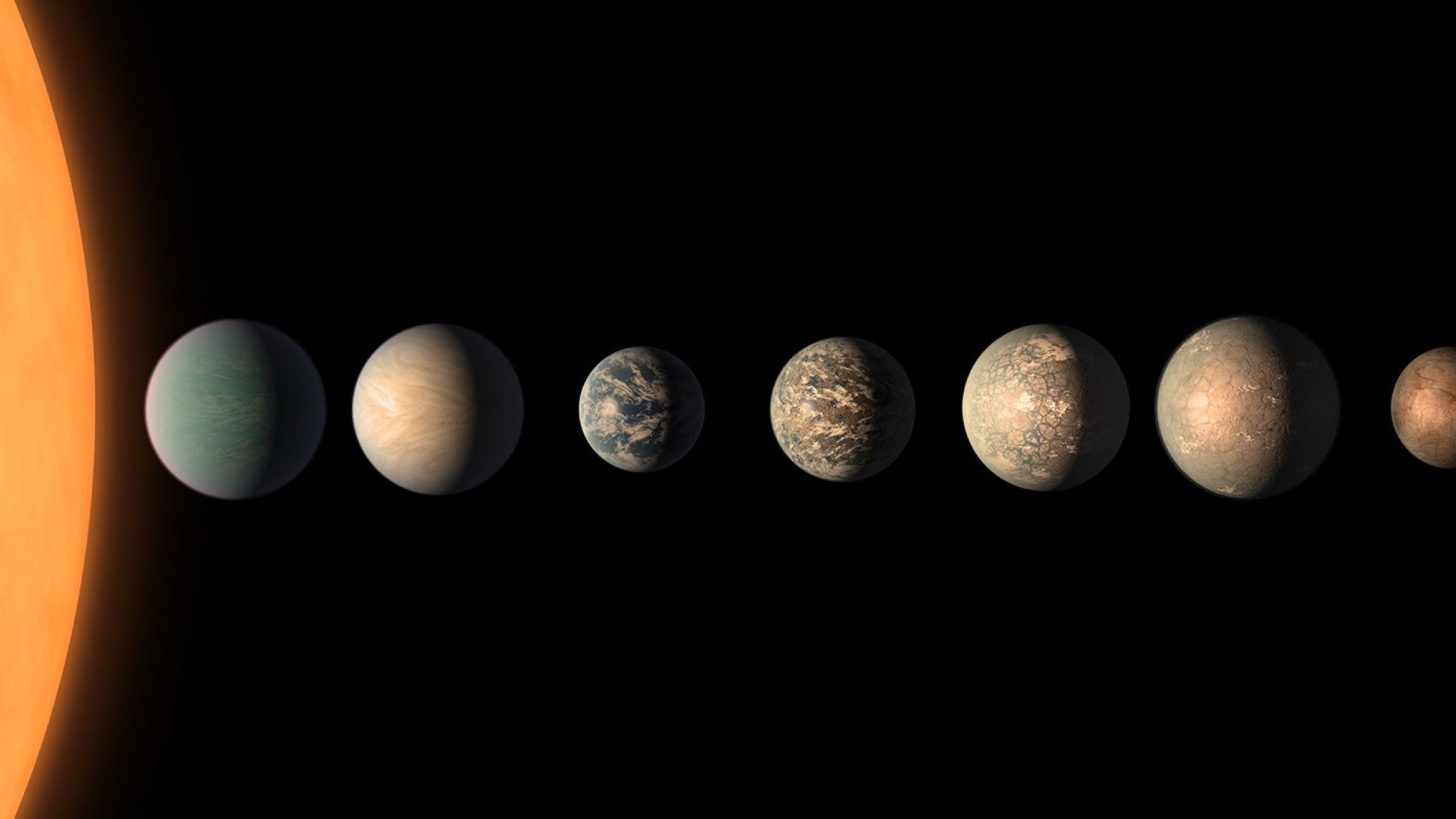

Observers have centered a lot consideration on TRAPPIST-1c for a great cause: it’s by far the most effective goal to review rocky, Earth-sized planets intimately, because it’s close by (about 40 gentle years away) and simple to see with present tech. “You would obviously start with the lowest-hanging fruit,” says Zieba. TRAPPIST-1c orbits the star TRAPPIST-1, which hosts a household of seven Earth-sized planets. Three of them is likely to be within the star’s liveable zone.

That photo voltaic system provides a singular probability for astronomers to have a look at Earth-like planets at totally different temperatures, getting a glimpse at a spectrum of prospects for rocky worlds. By figuring out what molecules encompass these worlds, “we may be able to infer whether they could indeed support life,” says University of California, Los Angeles astronomer Judah Van Zandt, who was not concerned within the paper.

[Related: What Earth looks like to far-out celestial bodies]

TRAPPIST-1 isn’t like our solar, although. It’s a small purple star known as an M dwarf, which occurs to be the commonest star sort within the galaxy. One of the massive questions in astronomy proper now’s: Can planets round M dwarfs preserve their atmospheres, or do the brutal flares of those highly effective little stars burn the skies away? If astronomers discover that almost all planets round M dwarfs are naked rocks, perhaps sun-like stars are mandatory for all times in any case. So far, there are two strikes in opposition to M dwarfs—not solely does TRAPPIST-1c lack an environment, however a publication from earlier this yr confirmed that TRAPPIST-1b can also be barren.

We will quickly discover out whether or not TRAPPIST-1c’s neighbors observe this sample—or upend it. All seven TRAPPIST-1 planets shall be noticed with JWST throughout the yr, and it’s but to be seen if others might have stored their clouds. And even when they don’t, as Zieba says, “this is obviously just one M-type star.” Astronomers must observe many extra planets to really choose whether or not M dwarfs are match to help life.