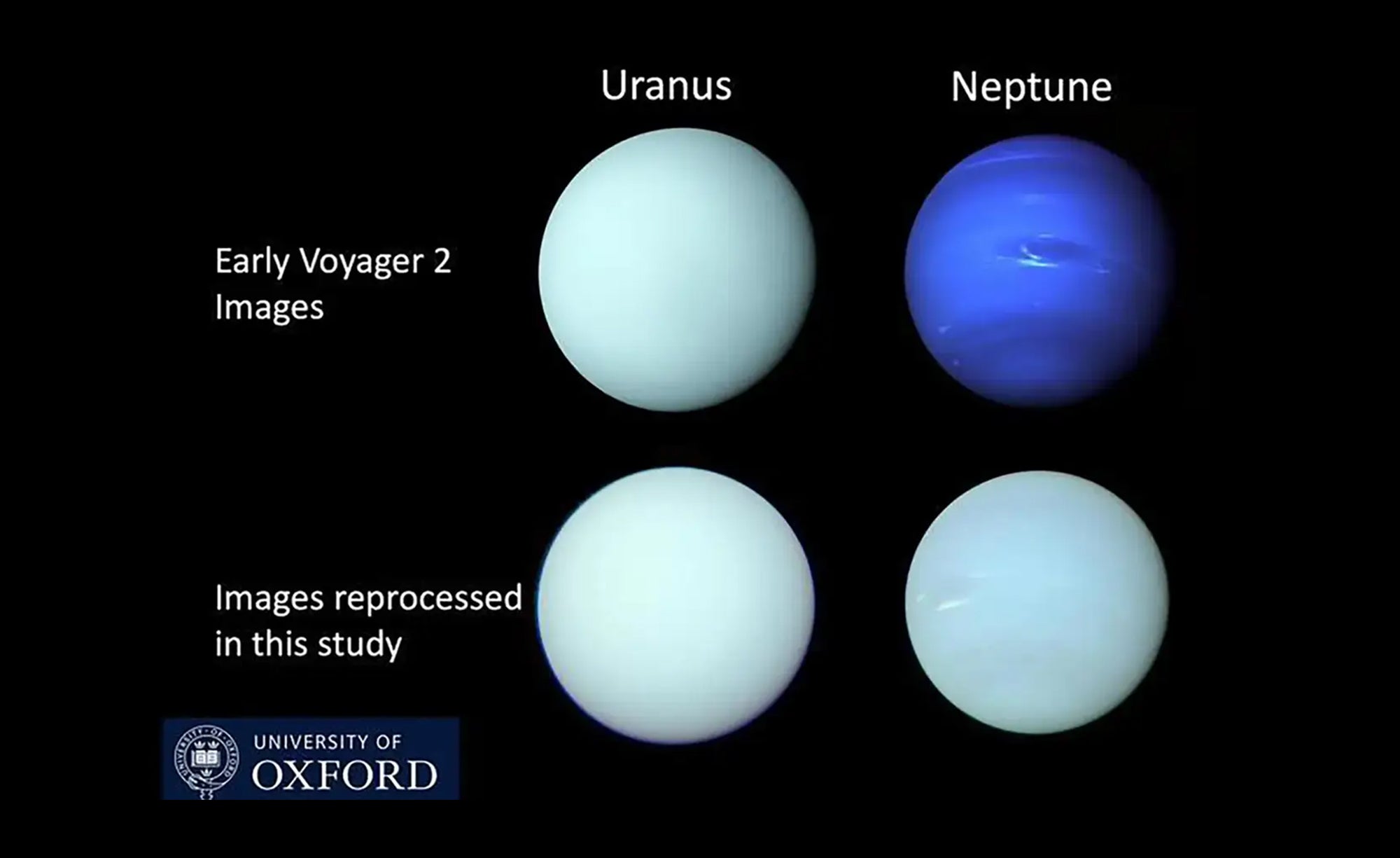

For many years, photographs taken of Neptune have appeared like the planet has a deep blue hue, whereas Uranus appeared extra inexperienced. However, these two ice giants may really look extra much like eachother than astronomers beforehand believed. According to a research printed January 5 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, our photo voltaic system’s furthest planets’ true colours might each be related pale shades of greenish blue.

[Related: The secret to Voyagers’ spectacular space odyssey.]

Images versus actuality

NASA’s Voyager 2 mission stays the one flyby of each ice giants performed by a spacecraft. It gave us the primary detailed photographs of those far-flung planets. Voyager 2 performed a flyby of Uranus in 1986, and the photographs revealed a planet with a extra pale cyan or blue shade. The vessel flew by Neptune in 1989 and the imagery confirmed a planet with a wealthy blue shade.

However, astronomers have lengthy understood that almost all fashionable photographs of each planets don’t precisely replicate their true colours. Voyager 2 captured photographs of every planet in separate colours and these single-color photographs have been then put collectively to make composites. These composite photographs weren’t at all times precisely balanced, notably for the planet Neptune which was believed to seem too blue. The distinction on the early Voyager photographs of Neptune have been additionally strongly enhanced to higher reveal the clouds and winds of the planet.

“Although the familiar Voyager 2 images of Uranus were published in a form closer to ‘true’ color, those of Neptune were, in fact, stretched and enhanced, and therefore made artificially too blue,” research co-author and University of Oxford astronomer Patrick Irwin mentioned in a press release. “Even though the artificially-saturated color was known at the time amongst planetary scientists–and the images were released with captions explaining it–that distinction had become lost over time.”

Creating a extra correct view

In the brand new research, the group utilized knowledge taken from the Hubble Space Telescope’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) and the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope.

With each the STIS and MUSE, every pixel is a steady spectrum of colours, so their observations may be processed extra clearly to find out the extra correct shade of the planets, as a substitute of what is being seen with a filter.

The group used the information to rebalance the composite shade photographs that have been recorded by Voyager 2’s onboard digicam and by the Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3. The rebalancing revealed that each Uranus and Neptune are literally the same pale shade of greenish blue. Neptune has a slight trace of extra blue, which the mannequin confirmed to be a skinny layer of haze on the planet.

The altering colours of Uranus

This analysis additionally offers a probable reply to why Uranus modifications shade barely throughout its 84 year-long orbit across the solar. The group first in contrast photographs of Uranus to measurements of its brightness that have been taken at blue and inexperienced wavelengths by the Lowell Observatory in Arizona from 1950 to 2016. These measurements confirmed that Uranus seems to be a little bit greener throughout its summer season and winter solstices, when its poles are pointed in the direction of the solar. However, throughout the equinoxes–when the solar is over the planet’s equator–it seems to have a extra blue tinge.

Patrick Irwin/University of Oxford

One already established cause for the change is as a result of Uranus’ a extremely uncommon spin. The planet spins nearly on its aspect throughout orbit, so its north and south poles level nearly straight in the direction of the solar and Earth throughout its solstices. Any modifications to the reflectivity of Uranus’ poles would have a serious affect on the planet’s total brightness when considered from the Earth, in line with the authors. What was much less clear to astronomers was how and why this reflectivity differs. The group developed a mannequin to check the bands of colours of Uranus’s polar areas to its equatorial areas.

They discovered that polar areas are extra reflective at inexperienced and crimson wavelengths than at blue wavelengths. Uranus is extra reflective at these wavelengths partially as a result of fuel methane absorbs the colour crimson and methane is about half as ample close to Uranus’ poles than the equator.

[Related: Neptune’s bumpy childhood could reveal our solar system’s missing planets.]

However, this wasn’t sufficient to totally clarify the colour change so the researchers added a brand new variable to the mannequin within the type of a ‘hood’ of step by step thickening icy haze which has beforehand been noticed when Uranus strikes from equinox to summer season solstice. They imagine that this haze is possible made up of methane ice particles.

After simulating this pole shift within the mannequin, the ice particles additional elevated the reflection at inexperienced and crimson wavelengths on the planet’s poles, which defined that Uranus seems to be greener on the solstice as a result of much less methane on the poles and elevated thickness of the methane ice particles.

“The misperception of Neptune’s color, as well as the unusual color changes of Uranus, have bedeviled us for decades,” Heidi Hammel, of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy mentioned in a press release. “This comprehensive study should finally put both issues to rest.” Hammel is not an creator of the brand new research.

Filling on this hole between the general public notion of Neptune and its actuality exhibits how knowledge may be manipulated to point out off sure options of a planet or improve visualizations.

“There’s never been an attempt to deceive,” research co-author and University of Leicester planetary scientist Leigh Fletcher advised The New York Times. “But there has been an attempt to tell a story with these images by making them aesthetically pleasing to the eye so that people can enjoy these beautiful scenes in a way that is, maybe, more meaningful than a fuzzy, gray, amorphous blob in the distance.”