This article was initially featured on MIT Press.

This article is tailored from Omar W. Nasim’s e-book “The Astronomer’s Chair: A Visual and Cultural History“.

When you shut your eyes and assume of a chair, what involves thoughts? You would possibly see your father’s favourite straightforward chair, the one he sank into to look at tv and which nonetheless holds the sturdy scent of his pipe tobacco; the couch you have been on if you first conquered “Mario Bros.”; or that particular sofa that at all times remained lined with a sheet or plastic slipcover till friends arrived.

Yet others would possibly see in their thoughts’s eye designer chairs like Le Corbusier’s chaise lounge, Charles and Ray Eames’s arm and facet chairs, or the ever-present plastic monobloc chairs banned by town of Basel in 2008—chairs that embody emblematic designs of the 20th century, to not point out fetishized industrial objects that proceed to encourage or repulse. Still others may think Van Gogh’s acquainted rustic wood chairs or the Iron Throne on the middle of the hit collection “Game of Thrones.” Whatever the case, it’s clear that the chair encapsulates much more than merely inert furnishings.

The chair is, in spite of everything, one of these inconspicuous helps, very like the ground beneath your ft or the partitions round you, that tends to fall away into the background as a way to get on with different issues, like studying. But if we attend to chairs in a scientific method and take them severely as objects of historic analysis, they open up a complete world of significance.

As indicators of stature, there are chairs in the history of science which have turn out to be iconic. These vary from Voltaire’s studying chair outfitted with candlestick holder and bookrest, to Benjamin Franklin’s library chair with built-in steps, to Charles Darwin’s armchair on wheels, nonetheless on show at his house workplace in Down House, Kent. Such relics are housed in museums visited by 1000’s yearly, for whom these artifacts sparkle with a historic and cultural aura, one associated to the standing of science in our fashionable societies. Think additionally of Stephen Hawking’s wheelchair, which, after the celebrated astrophysicist’s demise in 2018, was initially regarded as certain for the Science Museum in London, however was purchased at Christie’s public sale home in London for $390,000 and ended up in non-public fingers as an alternative. Or the nook chair made someday in the early Nineteenth century from the wooden of the legendary apple tree at Woolsthorpe Manor underneath which Newton is alleged to have sat.

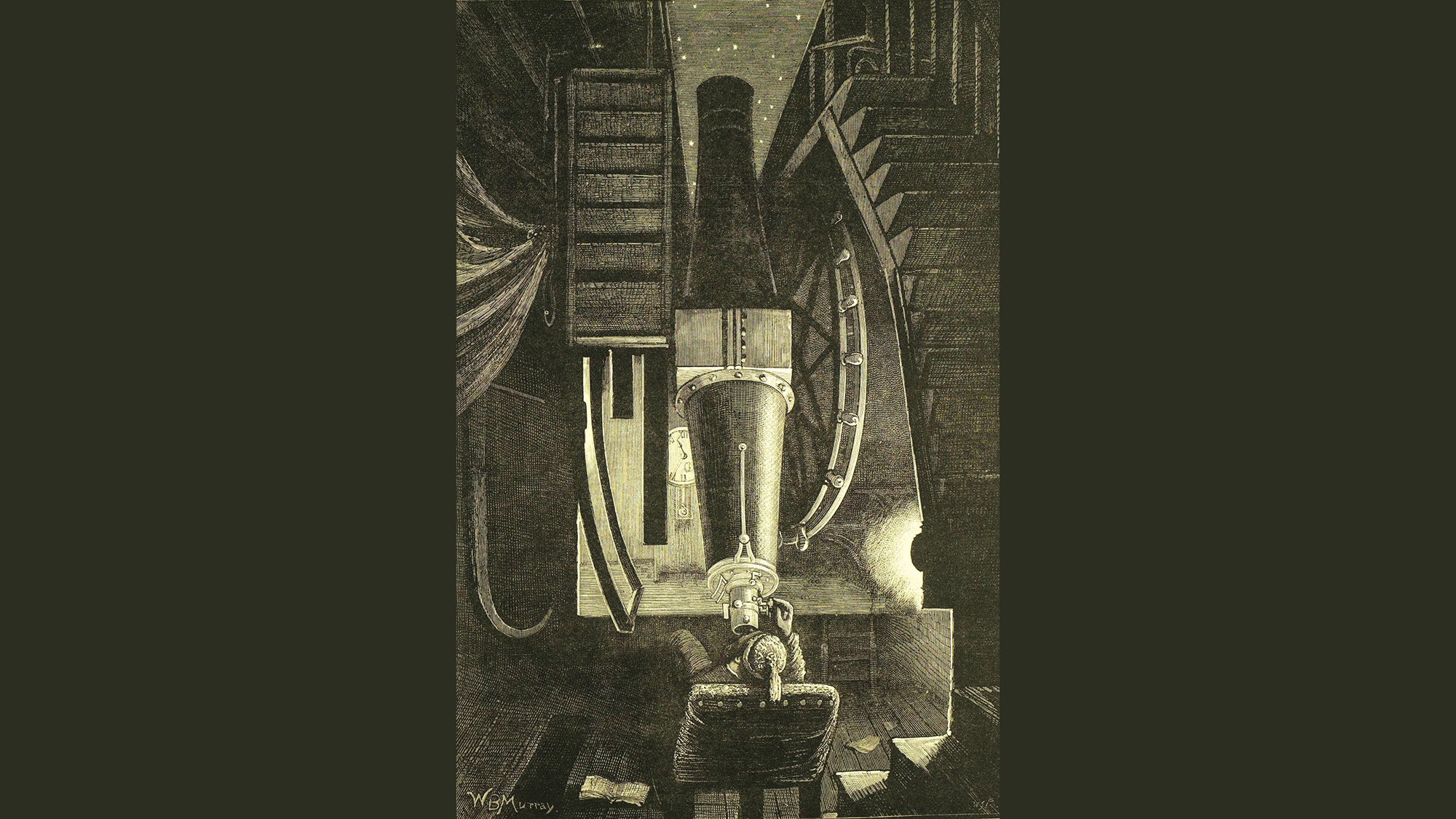

At all these ranges—from the mundane to the enduring, from the bodily to the symbolic, the true and mythic—the hanging presence of chairs in the history of science begs to be acknowledged and understood. As a historian of science motivated by the work of cultural historians of design and furnishings, I sought to discover the importance of specialised chairs utilized by astronomers in my e-book “The Astronomer’s Chair.” Why astronomers? The e-book grew out of a curious statement. In researching the roles of drawing and images in astronomy, I observed a recurring however beforehand unrecognized motif: representations of observing chairs particularly designed to be used by astronomers on the telescope. Once I began to note them, I noticed them all over the place. The photos typically confirmed an astronomer seated in a custom-built chair. At different instances, the specialised chair was staged empty however alongside different cutting-edge devices of an observatory.

The astronomer’s chair, too, seems to have a protracted history.

At least way back to the mid-14th century we discover a hexagonal panel aid initially crafted in the workshops of Andrea Pisano for Giotto’s Campanile in Florence. It is a panel—now in the Museo dell‘Opera del Duomo—that shows Gionitus, the mythical founder of astronomy, seated at a desk operating a quadrant while taking notes. There is also the 1493 engraved portrayal of the ninth-century Baghdad astronomer al-Farghānī (800/805–870 CE) seated on a bench next to a diminutive figure of a hermit in a Latin translation of his important work. Albrecht Dürer’s frontispiece to “De scientia motus orbis” (1504), a Latin translation of the eighth-century Arabic astronomical textual content by the Persian-Jewish astronomer Māshā’allāh ibn Athari (740–815 CE), exhibits the latter in a peculiar however presumably specialised chair holding a globe and compass.

We discover illuminated codices depicting well-seated astronomers, such because the likeness of Ptolemy that decorates the title web page of “Ptolemaeus: Magna Compositio, Zierrahmen mit Tugenden und dem Wappen” (1465). Ptolemy is proven topped and seated like a king upon a throne whereas holding a compass. But among the many most well-known depictions is definitely the 1598 engraving of Tycho Brahe that renders the well-known astronomer put in in the center of his famend observatory on the island of Hven.

Besides Johannes Vermeer’s 1668 oil-on-canvas portray of “The Astronomer” or the intricate engraving of the German Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius by E. de Boulonois, the seventeenth century witnessed an abundance of photos of astronomers with their telescopes, presumably at work. We might also assume of the well-known print of the octagon room of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich from 1676.

The 18th century noticed such photos improve in quantity. Among the well-known is the 1735 depiction of the Danish astronomer Ole Rømer seated on a low cushioned stool working along with his progressive meridian telescope. There is the splendidly lush mezzotint of the Austrian astronomer Maximilian Hell seated subsequent to his instrument and decked out in his warmest Lappish winter apparel (1771); the mezzotint of Thomas Phelps and John Bartlett which presents the 2 at work: one wanting by way of a telescope, whereas the opposite, seated on an observing chair, takes notes (1778); and the oil-on-canvas portrait by the painter Charles W. Peale (1796) of the American astronomer David Rittenhouse seated subsequent to a telescope on a desk.

We can multiply examples indefinitely, for as we strategy the Nineteenth century the amount of representations begins to considerably improve in quantity and presence, however so do the quantity of bodily chairs designed for the needs of astronomical statement. In researching the e-book, I discovered a whole bunch of these photos from that century and the following, and discerned that the upsurge in depictions corresponded to a rising concern for the use, design, and building of such chairs by astronomers themselves.

With such an prolonged visible timeline, a sensitivity to a number of representations and their totally different sociocultural contexts can be utilized to broach an iconographic history that implicates the picture of science, the character of its labors, and the personae of the astronomer for a given interval. But as an alternative of presenting and analyzing the whole history of these photos—an formidable iconographic challenge for a extra in depth and conclusive research—I restrict myself in “The Astronomer’s Chair” to solely a snapshot from this history, in a bid to supply the primary concentrated look into how one would possibly go about unraveling the cultural significance of the chair and its representations in Nineteenth-century astronomy and design.

According to Asa Briggs, the preeminent historian of all issues Victorian, objects like chairs are “emissaries” of meanings from which we will reconstruct bygone ages, certainly, different “intelligible universes.” Given how eagerly astronomers appeared to stage observing chairs and to pose in them throughout this era, I wished to know what message they have been making an attempt to ship to their audiences; how these performances have been learn by Nineteenth-century spectators; how they knowledgeable perform and design; and what they stated concerning the cultural place of astronomy in specific, and science extra typically. What I discovered was each shocking and illuminating. By observing chairs as topoi and indicators of far more than what first meets the attention, we acquire interdisciplinary insights into a range of beforehand well-studied themes—gender, historicism, labor, and race—linked to the cultural history of the lengthy Nineteenth century, reworking them into wealthy sources for histories of each science and furnishings.

Omar W. Nasim is Professor for the History of Science on the Institute of Philosophy on the University of Regensburg, Germany. He is the creator of “Observing by Hand: Sketching the Nebulae in the Nineteenth Century” (University of Chicago Press) and “The Astronomer’s Chair,” from which this text is tailored.