The Dark Ages weren’t completely darkish. Advances in agriculture and constructing expertise elevated Medieval wealth and led to a wave of cathedral building in Europe. However, it was a time of profound inequality. Elites captured nearly all financial positive aspects. In Britain, as Canterbury Cathedral soared upward, peasants had no web enhance in wealth between 1100 and 1300. Life expectancy hovered round 25 years. Chronic malnutrition was rampant.

“We’ve been struggling to share prosperity for a long time,” says MIT Professor Simon Johnson. “Every cathedral that your parents dragged you to see in Europe is a symbol of despair and expropriation, made possible by higher productivity.”

At a look, this may not appear related to life in 2023. But Johnson and his MIT colleague Daron Acemoglu, each economists, suppose it’s. Technology drives financial progress. As improvements take maintain, one perpetual query is: Who advantages?

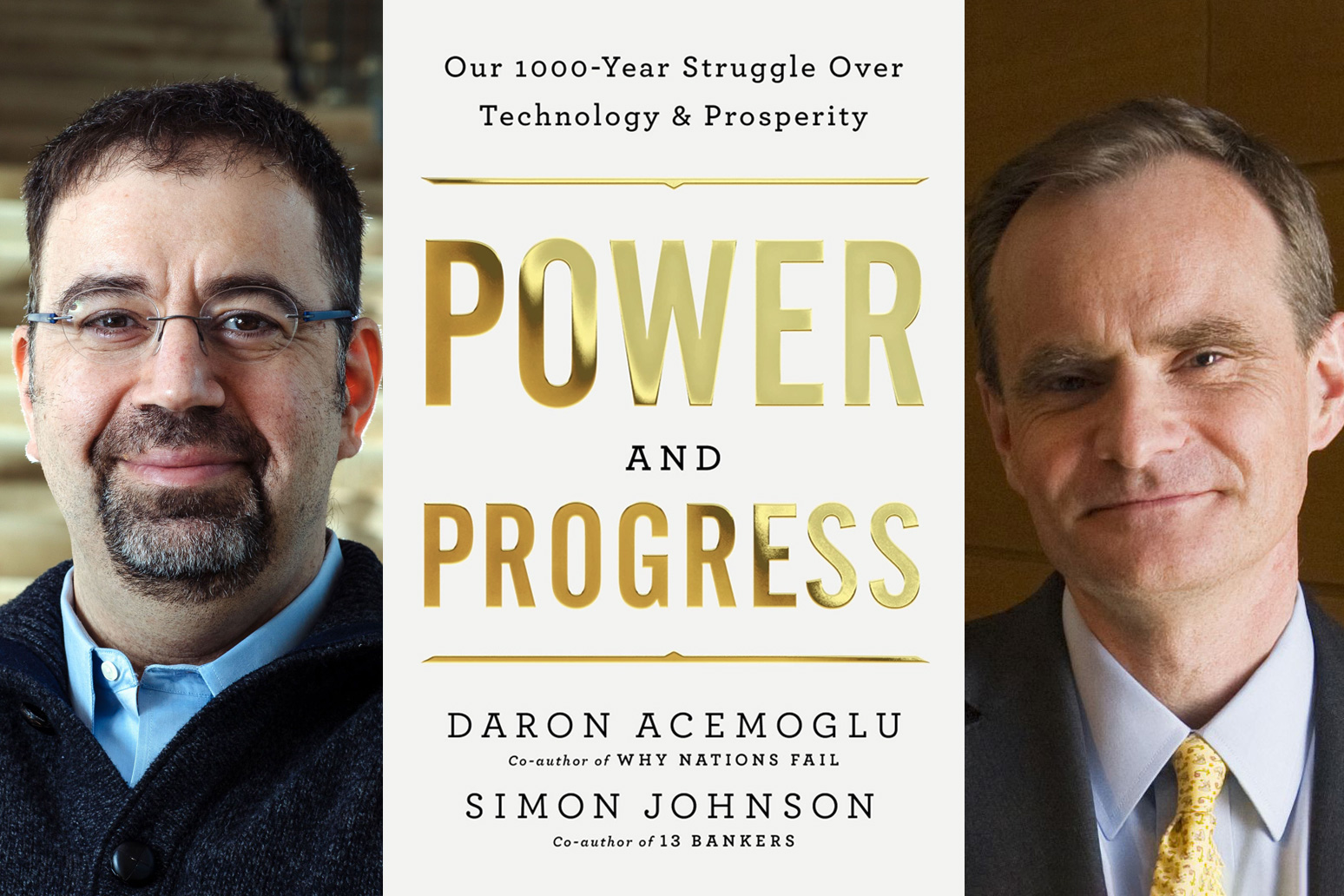

This applies, the students imagine, to automation and synthetic intelligence, which is the main focus of a brand new e book by Acemoglu and Johnson, “Power and Progress: Our 1000-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity,” printed this week by PublicAffairs. In it, they look at who reaped the rewards from previous improvements and who could acquire from AI at the moment, economically and politically.

“The book is about the choices we make with technology,” Johnson says. “That’s a very MIT type of theme. But a lot of people feel technology just descends on you, and you have to live with it.”

AI may develop as a useful power, Johnson says. However, he provides, “Many algorithms are being designed to try to replace humans as much as possible. We think that’s entirely wrong. The way we make progress with technology is by making machines useful to people, not displacing them. In the past we have had automation, but with new tasks for people to do and sufficient countervailing power in society.”

Today, AI is a instrument of social management for some governments that additionally creates riches for a small variety of individuals, based on Acemoglu and Johnson. “The current path of AI is neither good for the economy nor for democracy, and these two problems, unfortunately, reinforce each other,” they write.

A return to shared prosperity?

Acemoglu and Johnson have collaborated earlier than; within the early 2000s, with political scientist James Robinson, they produced influential papers about politics and financial progress. Acemoglu, an Institute Professor at MIT, additionally co-authored with Robinson the books “Why Nations Fail” (2012), about political establishments and progress, and “The Narrow Corridor” (2019), which casts liberty because the never-assured consequence of social battle.

Johnson, the Ronald A. Kurtz Professor of Entrepreneurship on the MIT Sloan School of Management, wrote “13 Bankers” (2010), about finance reform, and, with MIT economist Jonathan Gruber, “Jump-Starting America” (2019), a name for extra funding in scientific analysis.

In “Power and Progress,” the authors emphasize that expertise has created outstanding long-term advantages. As they write, “we are greatly better off than our ancestors,” and “scientific and technological progress is a vital part of that story.”

Still, loads of struggling and oppression has occurred whereas the long run is unfolding, and never simply throughout Medieval instances.

“It was a 100-year struggle during the Industrial Revolution for workers to get any cut of these massive productivity gains in textiles and railways,” Johnson observes. Broader progress has come by elevated labor energy and electoral authorities; when the U.S. financial system grew spectacularly for 3 a long time after World War II, positive aspects had been extensively distributed, although that has not been the case not too long ago.

“We’re suggesting we can get back onto that path of shared prosperity, reharness technology for everybody, and get productivity gains,” Johnson says. “We had all that in the postwar period. We can get it back, but not with the current form of our machine intelligence obsession. That, we think, is undermining prosperity in the U.S. and around the world.”

A name for “machine usefulness,” not “so-so automation”

What do Acemoglu and Johnson suppose is poor about AI? For one factor, they imagine the event of AI is simply too centered on mimicking human intelligence. The students are skeptical of the notion that AI mirrors human pondering all advised — even issues just like the chess program AlphaZero, which they regard extra as a specialised set of directions.

Or, for example, picture recognition applications — Is {that a} husky or a wolf? — use massive knowledge units of previous human choices to construct predictive fashions. But these are sometimes correlation-dependent (a husky is extra more likely to be in entrance of your own home), and can’t replicate the identical cues humans depend on. Researchers know this, after all, and hold refining their instruments. But Acemoglu and Robinson contend that many AI applications are much less agile than the human thoughts, and suboptimal replacements for it, at the same time as AI is designed to exchange human work.

Acemoglu, who has printed many papers on automation and robots, calls these alternative instruments “so-so technologies.” A grocery store self-checkout machine doesn’t add significant financial productiveness; it simply transfers work to prospects and wealth to shareholders. Or, amongst extra refined AI instruments, for example, a customer support line utilizing AI that doesn’t handle a given downside can frustrate individuals, main them to vent as soon as they do attain a human and making the entire course of much less environment friendly.

All advised, Acemoglu and Johnson write, “neither traditional digital technologies nor AI can perform essential tasks that involve social interaction, adaptation, flexibility, and communication.”

Instead, growth-minded economists desire applied sciences creating “marginal productivity” positive aspects, which compel companies to rent extra staff. Instead of aiming to get rid of medical specialists like radiologists, a much-forecast AI growth that has not occurred, Acemoglu and Johnson counsel AI instruments may develop what residence well being care staff can do, and make their companies extra beneficial, with out lowering staff within the sector.

“We think there is a fork in the road, and it’s not too late — AI is a very good opportunity to reassert machine usefulness as a philosophy of design,” Johnson says. “And to look for ways to put tools in the hands of workers, including lower-wage workers.”

Defining the dialogue

Another set of AI points Acemoglu and Johnson are involved about lengthen immediately into politics: Surveillance applied sciences, facial-recognition instruments, intensive knowledge assortment, and AI-spread misinformation.

China deploys AI to create “social credit” scores for residents, together with heavy surveillance, whereas tightly proscribing freedom of expression. Elsewhere, social media platforms use algorithms to affect what customers see; by emphasizing “engagement” above different priorities, they can unfold dangerous misinformation.

Indeed, all through “Power and Progress,” Acemoglu and Johnson emphasize that the usage of AI can arrange self-reinforcing dynamics through which those that profit economically can acquire political affect and energy on the expense of wider democratic participation.

To alter this trajectory, Acemoglu and Johnson advocate for an in depth menu of coverage responses, together with knowledge possession for web customers (an concept of technologist Jaron Lanier); tax reform that rewards employment greater than automation; authorities help for a variety of high-tech analysis instructions; repealing Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, which protects on-line platforms from regulation or authorized motion primarily based on the content material they host; and a digital promoting tax (aimed to restrict the profitability of algorithm-driven misinformation).

Johnson believes individuals of all ideologies have incentives to help such measures: “The point we’re making is not a partisan point,” he says.

Other students have praised “Power and Progress.” Michael Sandel, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government at Harvard University, has known as it a “humane and hopeful book” that “shows how we can steer technology to promote the public good,” and is “required reading for everyone who cares about the fate of democracy in a digital age.”

For their half, Acemoglu and Johnson need to broaden the general public dialogue of AI past trade leaders, discard notions concerning the AI inevitability, and suppose once more about human company, social priorities, and financial prospects.

“Debates on new technology ought to center not just on the brilliance of new products and algorithms but on whether they are working for the people or against the people,” they write.

“We need these discussions,” Johnson says. “There’s nothing inherent in technology. It’s within our control. Even if you think we can’t say no to new technology, you can channel it, and get better outcomes from it, if you talk about it.”