A e-book co-written by an MIT professor takes a single line of code — the concise BASIC program for the Commodore 64, which additionally serves because the e-book’s title — and makes use of it as a lens to look at each the phenomenon of inventive computing and laptop packages in tradition.

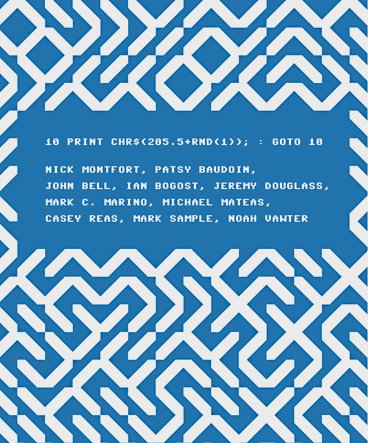

The e-book’s title, “10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10” (MIT Press, 2012), doesn’t precisely roll off the tongue. But as laptop code, it has the standard of concrete poetry in the eyes of Nick Montfort, affiliate professor of digital media in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies/Writing program and the e-book’s lead writer.

Written for the Commodore 64, one of many earliest private computer systems (launched in 1982), the phrase “10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10” is a line of code in BASIC, the primary extensively widespread programming language designed to be used by non-scientists. When executed, the code randomly, and repeatedly, generates both a / or a , filling the display with a sample that resembles a maze.

“The emergent complexity from this deceptively simple work is part of its interest,” says Montfort, noting that whereas not all code may be thought of poetic, 10 PRINT is particular. “I believe it is a concrete poem, a found poem. It’s a cultural artifact.”

Montfort identifies laptop code in normal as a culturally vital human language, simply as deserving of shut vital evaluation as different merchandise of tradition. “No one would be startled to ask why a particular word is used in a literary text,” Montfort says. “Why can’t we do that with a line of code?”

Language that executes

Despite the title, “10 PRINT” is just not a technical e-book of curiosity solely to programmers. Instead, the code is used as a leaping off level for inspecting a variety of humanities questions, together with the function the code’s maze performs in Western tradition, and randomness in computing and the humanities.

The authors even plumbed the depths of the code by inspecting it in translation, that means to attempt it out in different programming languages (a course of referred to as porting). They found, for instance, that in some languages the characters from completely different strains don’t contact one another, and so no maze is fashioned. “This allows us to see why this is a particularly pleasing program on the Commodore,” Montfort says.

Going to such lengths as to look at one small piece of code is a invaluable train, Montfort says, as a result of “code is a language that executes. It can have various kinds of significance, from artistic to economic to political.”

He points out that the content of code has already made headlines, such as when the source code for Diebold voting machines was leaked in 2003, and when hackers unveiled code from Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom, fueling reports that anthropogenic climate change was a hoax.

“We’re arguing that code is culturally significant — and that larger scale models of scholarship can be brought to bear on [fundamental] questions,” Montfort says.

This work is central to the brand new wave of analysis referred to as “digital humanities,” he provides. “The intersection of digital and humanities is not just in new modes of presenting scholarship, it’s not just in ways computer techniques can be used to study materials — it’s also in understanding the ways computation and digital media have been transforming the culture.”

‘Massively co-authored scholarship’

“10 PRINT” (the e-book) emerged from a web-based workshop organized by the Critical Code Studies Group, a collaborative convention targeted on making use of vital idea and hermeneutics (the research of the interpretation of written texts) to the interpretation of laptop supply code. Invited to contribute code for dialogue, Montfort submitted the one-line 10 PRINT code, which he remembered from his childhood.

His submit sparked a full of life dialogue amongst a variety of specialists — in artwork, writing, digital media, laptop science and even library science. Montfort, who beforehand co-authored “Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System” (MIT Press, 2009), rapidly acknowledged the potential for a e-book on the subject.

He then tapped key contributors to hitch him in what he calls a “massively co-authored scholarship.” In complete, “10 PRINT” has 10 authors, together with Montfort and Patsy Baudoin, MIT Libraries liaison to the MIT Media Lab. Additional authors embrace John Bell; Ian Bogost; Jeremy Douglass; Mark C. Marino; Michael Mateas; Casey Reas SM ’01; Mark Sample; and Noah Vawter SM ’06, PhD ’11.

Even so, the e-book is just not a set of essays by 10 completely different folks, however one coherent narration, informed in one voice. “We had a wiki and wrote it together. Certain people would be lead writers for certain chapters, and there was an internal review process,” Montfort says. “It was a very complex process.”

Story ready by MIT SHASS Communications

Editorial and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Senior Writer: Kathryn O’Neill