Just about anyplace you look, there are birds. Penguins reside in Antarctica, ptarmigan in the Arctic Circle. Rüppell’s vultures soar greater than Mt. Everest. Emperor penguins dive deeper than 1,800 ft. There are birds on mountains, birds in cities, birds in deserts, birds in oceans, birds on farm fields, and birds in parking heaps.

Given their ubiquity—and the enjoyment many individuals get from seeing and cataloging them—birds supply one thing that units them other than different creatures: an abundance of knowledge. Birds are lively year-round, they arrive in many shapes and colours, they usually are comparatively easy to establish and interesting to watch. Every 12 months world wide, beginner birdwatchers report hundreds of thousands of sightings in databases that are out there for evaluation.

All that monitoring has revealed some sobering developments. Over the final 50 years, North America has misplaced a 3rd of its birds, research counsel, and most fowl species are in decline. Because birds are indicators of environmental integrity and of how different, much less scrutinized species are doing, knowledge like these needs to be a name to motion, says Peter Marra, a conservation biologist and dean of Georgetown University’s Earth Commons Institute. “If our birds are disappearing, then we’re cutting the legs off beneath us,” he says. “We’re destroying the environment that we depend on.”

It’s not all dangerous information for birds: Some species are rising in number, knowledge present, and dozens have been saved from extinction. Understanding each the steep declines and the success tales, specialists say, may assist to tell efforts to guard birds in addition to different species.

The dangerous information

On his day by day walks at daybreak alongside a path that snakes by a number of reservoirs close to his residence in central England, Alexander Lees sometimes sees a spread of widespread waterfowl: Canada geese, mallards, an occasional goosander, a kind of diving duck. Every as soon as in some time, he spots one thing uncommon: a northern gannet, a kittiwake, or a black tern. Lees, a conservation biologist at Manchester Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom, information every sighting in eBird, an internet guidelines and rising, international fowl database.

Lees research birds for a residing, however the overwhelming majority of those that observe the world’s 11,000 or so fowl species, both on their very own or as half of organized occasions, don’t. Hundreds of hundreds of them take part every year in the Great Backyard Bird Count, launched by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society in 1998: For 4 days every February, folks tally their sightings and the info are entered into eBird or a associated identification app for freshmen known as Merlin.

The North American Breeding Bird Survey, organized by the US Geological Survey and Environment Canada, has enlisted hundreds of contributors to watch birds alongside roadsides every June since 1966. Audubon’s Christmas Bird Count, which started in 1900, encourages folks to hitch a one-day fowl tally scheduled in a three-week window through the vacation season. There are shorebird censuses and waterfowl surveys, all powered by citizen scientists.

This wealth of longitudinal recordings began to show up indicators of misery way back to 1989, Marra says, when researchers analyzed knowledge from the North American Breeding Bird Survey and concluded that declines had been occurring amongst most of the species that breed in forests of the jap United States and Canada, then migrate to the tropics.

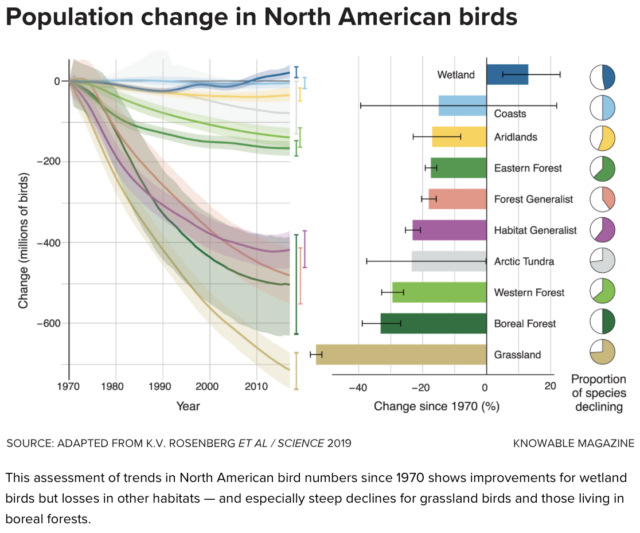

Thirty years later, Marra and colleagues reassessed the scenario utilizing a number of bird-monitoring datasets from North America together with knowledge on nocturnal fowl migrations from climate radars. They discovered gorgeous losses. Since 1970, the staff reported in Science in 2019, the number of birds in North America has declined by practically 3 billion: a 29 p.c loss of abundance. The paper used a number of strategies for estimating modifications in inhabitants sizes, Marra says, and “they all told us the same thing, which was that we’re watching the process of extinction happen.”

More than half of the 529 fowl species assessed by the research have declined, the staff reported, with the steepest drops in grassland birds, which have suffered from habitat loss and our use of pesticides. Declines are widespread amongst many widespread and plentiful species that play necessary roles in meals webs, Marra provides.

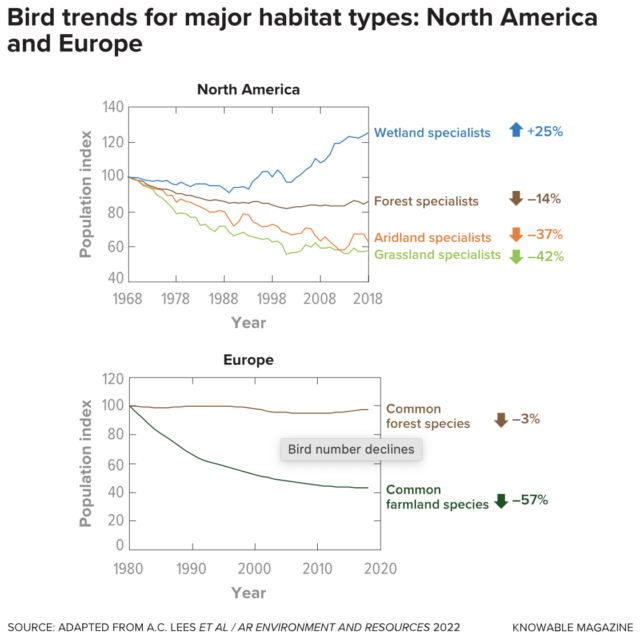

And it’s not simply North America. In the European Union, a 2021 research of 378 species estimated that fowl numbers fell by as a lot as 19 p.c from 1980 to 2017. Data are scarcer on different continents, however experiences are beginning to chronicle issues elsewhere, too. At least half of the birds that rely upon South Africa’s forests have skilled shrinking ranges (with inhabitants developments but to be assessed).

In Costa Rica’s agricultural areas, an evaluation of 112 fowl populations discovered extra are declining than are rising or remaining steady, in line with a 12-year research of espresso plantations and forest fragments that was printed in 2019. Meanwhile, at 55 websites in the Amazon, 11 p.c of surveyed insect-eating birds have skilled shrinking ranks, some of them dramatically, over greater than 35 years of monitoring. Of 79 species on which there have been sufficient knowledge to check historic and up to date numbers in main forests, eight have dwindled by not less than 50 p.c.

And in India, utilizing citizen science knowledge from eBird, a 2020 report estimated shrinking numbers in 80 p.c of the 146 species examined—practically half with declines of greater than 50 p.c. Overall, 13 p.c of birds worldwide are threatened with extinction, in line with the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List, a complete supply of data on the extinction danger of the world’s plant, animal, and fungus species.

Recently, Lees and colleagues pulled collectively all the info they might discover on the state of the world’s birds, publishing in the 2022 Annual Review of Environment and Resources. It was an try to, for the primary time, synthesize analysis from the world over to create a complete image of international modifications in fowl abundance. “Looking across all taxa, there are big signals for declines everywhere,” Lees says. “There are some species which are increasing, but more species are declining than are increasing. In our attempts to halt the loss of global bird biodiversity, we’re currently not succeeding.”

Silver linings

Even as they reveal a downward slide, fowl surveys supply some hopeful indicators. Wetland species in North America have grown by 13 p.c since 1970, in line with the 2019 Science research, led by a 56 p.c rise in waterfowl numbers. The paper credit billions of {dollars} allotted to the safety and restoration of wetlands, typically for the sake of searching. In India, 14 p.c of assessed fowl species have been rising in abundance. Those successes, scientists say, present that it’s potential to reverse inhabitants declines.

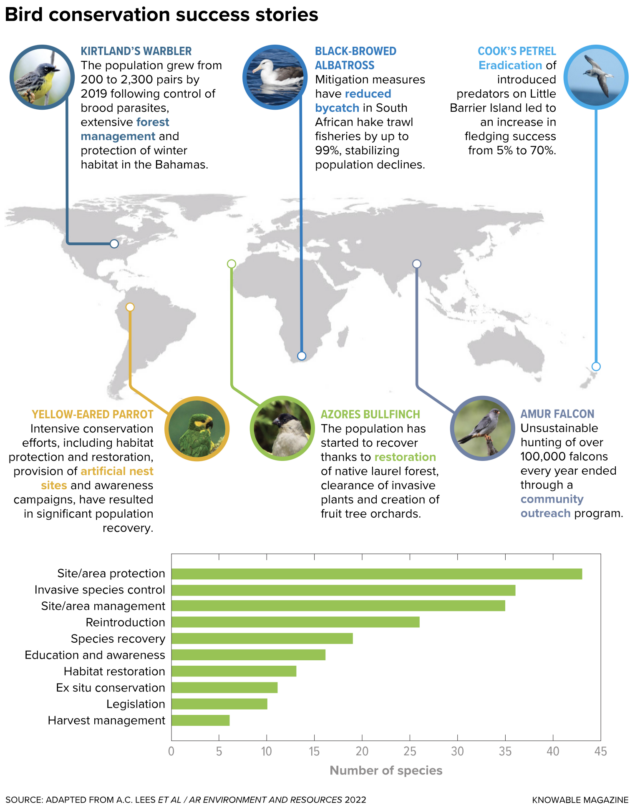

There are a lot of examples of birds which have been saved from extinction by folks, provides Philip McGowan, a conservation scientist at Newcastle University in the UK. To assess the impacts of conservation actions, he and colleagues made a listing of fowl and mammal species that had been listed as endangered or extinct in the wild on the IUCN Red List at any level since 1993.

For every species, they collected as a lot data as they might about inhabitants developments, pressures driving the species to extinction, and key selections or actions taken to guard them. Over daylong Zoom calls, small teams of researchers hashed out the small print earlier than everybody assigned every species a rating indicating how assured they had been that conservation actions had influenced the species’ standing.

For some birds, the researchers had been in a position to definitively hyperlink conservation efforts with species survival. The Spix’s macaw, for instance, has continued to exist solely as a result of it has been stored in captivity. And the California condor clearly benefited from the ban of lead ammunition, in addition to captive breeding packages and reintroductions, amongst different measures.

But for different species, there was much less certainty. The red-billed curassow of jap Brazil, for one, faces threats of habitat fragmentation and searching. Protected areas meant to safeguard it aren’t all the time effectively enforced, making it possible however much less clear that conservation has helped the species.

Overall, the researchers reported in 2020, as many as 48 species of birds and mammals had been saved from extinction between 1993 and 2020 (McGowan says that’s more likely to be an underestimate). The number of extinctions, the calculations confirmed, would have been three or 4 instances greater or extra with out human intervention.

Those findings ought to supply hope and motivation to assist extra species, McGowan says. “If we look at what has worked, we know that we can avoid extinctions,” he says. “We just need to scale that up.”

Forging forward

In 2020, the 12 months after Marra and colleagues reported a loss of practically a 3rd of North American birds, they partnered with a number of conservation teams to launch the Road to Recovery Initiative. The venture has recognized 104 species of birds in the United States and Canada that want rapid assist and, of these, 30 that are extremely susceptible to extinction as a result of of extraordinarily small inhabitants sizes or precipitous declines.

For every species, Marra says, it will likely be necessary to be taught what’s behind their shrinking populations. Currently, he says, “We’re not approaching conservation from a species perspective. And people are nervous about doing that … they view it as being just too difficult. But I maintain that we can figure it out, just like we’ve done with … all the species that almost disappeared because of DDT. We have the power and the understanding with new science and with new quantitative skills to identify the causes of decline and to figure out how we can eliminate those.”

It will take political will to put aside sources and enact widescale modifications, comparable to lowering chemical use on farms, Lees says. Saving extra birds, he provides, would ideally entail focusing as a lot vitality on woodlands and agricultural areas as governments have allotted to wetlands, in addition to implementing conservation measures effectively earlier than the purpose the place a species is about to vanish. “What we’re not succeeding at doing,” he says, “is stopping lots of species from getting rarer.”

Policies have to acknowledge the pursuits of native communities, provides McGowan. That’s a key focus of a brand new worldwide settlement that was cast on the finish of 2022, when representatives from 188 governments met in Montreal for the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) and adopted a set of measures to cease biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and defend Indigenous rights.

Involving native folks can profit biodiversity whereas respecting communities, McGowan says. In South America, for instance, the yellow-eared parrot practically went extinct, in half as a result of folks decimated palm groves, which are prime nesting habitats for the birds, to make use of the fronds in Palm Sunday processions. Successful conservation actions have included a neighborhood outreach marketing campaign that inspired folks to cease reducing down wax palms and stop searching the parrots. In 2003, the top of Colombia’s Catholic church halted a 200-year-old Palm Sunday custom involving wax palms, and parrot numbers have since elevated. “Working with local people meant that threat could be reduced,” McGowan says. Conservation, he says, ought to goal the species that want motion most urgently whereas making certain that native folks are not disenfranchised.

Better inhabitants estimates would assist to tell conservation efforts, says Corey Callaghan, a worldwide ecologist on the University of Florida in Davie. As it stands, broad margins of error are an issue, in half as a result of estimating abundance is difficult and the sampling knowledge are full of biases. Large birds are overrepresented in some sorts of citizen science knowledge, Callaghan discovered in a 2021 research. And since contributors to the North American Breeding Bird Survey stand on the perimeters of roads in the daytime, Marra says, they miss nocturnal birds, marshland birds and birds that reside in untouched landscapes.

Understanding and accounting for these biases may result in higher estimates, says Callaghan. In one instance of how far off counts might be, complete estimates of shorebirds known as Asian dowitchers ranged from 14,000 to 23,000—till a survey in 2019 tallied greater than 22,000 of the birds on a single wetland in jap China. Researchers can’t assess modifications in the event that they don’t have correct baseline estimates, says Callaghan. To that finish, he argues for extra open sharing of databases and extra integration of observations collected by researchers and citizen scientists. “If we want to preserve what we have around us,” he says, “we need to understand how much there is and how much we’re losing.”

As extra knowledge emerge, researchers urge optimism. “It’s really important not to have a doomsayer sort of position,” Lees says. Conservation has saved very uncommon species from extinction, he notes, and reversed declines in once-common species.

“Conservation,” he says, “does work.”

Knowable Magazine, 2023. DOI: 10.1146/knowable-053123-3. (About DOIs)

Emily Sohn is a contract journalist in Minneapolis whose tales have appeared in National Geographic, the New York Times, Nature, and lots of different publications. Find her at www.tidepoolsinc.com.

This article initially appeared in Knowable Magazine, an unbiased journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the publication.