When the Brazilian dietary scientist Carlos Monteiro coined the time period “ultra-processed foods” 15 years in the past, he established what he calls a “new paradigm” for assessing the impression of weight loss plan on well being.

Monteiro had seen that though Brazilian households have been spending much less on sugar and oil, weight problems charges have been going up. The paradox may very well be defined by elevated consumption of meals that had undergone excessive ranges of processing, reminiscent of the addition of preservatives and flavorings or the removing or addition of vitamins.

But well being authorities and meals corporations resisted the hyperlink, Monteiro tells the FT. “[These are] people who spent their whole life thinking that the only link between diet and health is the nutrient content of foods … Food is more than nutrients.”

Monteiro’s meals classification system, “Nova,” assessed not solely the dietary content material of foods but additionally the processes they endure earlier than reaching our plates. The system laid the groundwork for twenty years of scientific analysis linking the consumption of UPFs to weight problems, most cancers, and diabetes.

Studies of UPFs present that these processes create meals—from snack bars to breakfast cereals to prepared meals—that encourages overeating however might depart the eater undernourished. A recipe would possibly, for instance, comprise a degree of carbohydrate and fats that triggers the mind’s reward system, which means you must devour extra to maintain the pleasure of consuming it.

In 2019, American metabolic scientist Kevin Hall carried out a randomized examine evaluating individuals who ate an unprocessed weight loss plan with those that adopted a UPF weight loss plan over two weeks. Hall discovered that the topics who ate the ultra-processed weight loss plan consumed round 500 extra energy per day, extra fats and carbohydrates, much less protein—and gained weight.

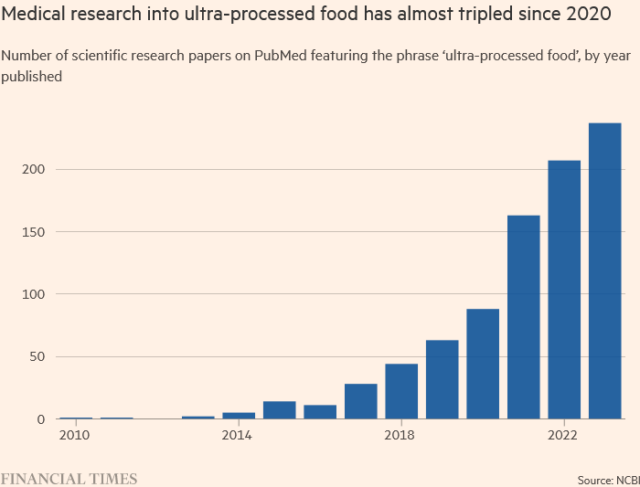

The rising concern about the well being impression of UPFs has recast the debate round meals and public well being, giving rise to books, coverage campaigns, and tutorial papers. It additionally presents the most concrete problem but to the enterprise mannequin of the meals trade, for whom UPFs are extraordinarily worthwhile.

The trade has responded with a ferocious marketing campaign in opposition to regulation. In half it has used the identical lobbying playbook as its struggle in opposition to labeling and taxation of “junk food” excessive in energy: huge spending to affect policymakers.

FT evaluation of US lobbying information from non-profit Open Secrets discovered that meals and comfortable drinks-related corporations spent $106 million on lobbying in 2023, virtually twice as a lot as the tobacco and alcohol industries mixed. Last 12 months’s spend was 21 % greater than in 2020, with the improve pushed largely by lobbying referring to meals processing in addition to sugar.

In an echo of techniques employed by cigarette corporations, the meals trade has additionally tried to stave off regulation by casting doubt on the analysis of scientists like Monteiro.

“The strategy I see the food industry using is deny, denounce, and delay,” says Barry Smith, director of the Institute of Philosophy at the University of London and a guide for corporations on the multisensory expertise of food and drinks.

So far the technique has proved profitable. Just a handful of nations, together with Belgium, Israel, and Brazil, presently confer with UPFs of their dietary pointers. But as the weight of proof about UPFs grows, public well being specialists say the solely query now could be how, if in any respect, it’s translated into regulation.

“There’s scientific agreement on the science,” says Jean Adams, professor of dietary public well being at the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge. “It’s how to interpret that to make a policy that people aren’t sure of.”