Today, Mars is chilly and dry. Billions of years in the past, nonetheless, there was liquid water on its floor—and scientists have lengthy been fascinated by what the planet may have been like at the moment. A new study, printed in Communications Earth and Environment on July 7, examines knowledge from soil samples gathered by NASA’s Curiosity rover and compares them to comparable soil on Earth. This supplies a window into what the Martian floor was like billions of years in the past—and the information suggests that it was that it was actually a chilly, wet wasteland of a planet.

[ Related: NASA’s Curiosity rover captures a moody Martian sunset for the first time ]

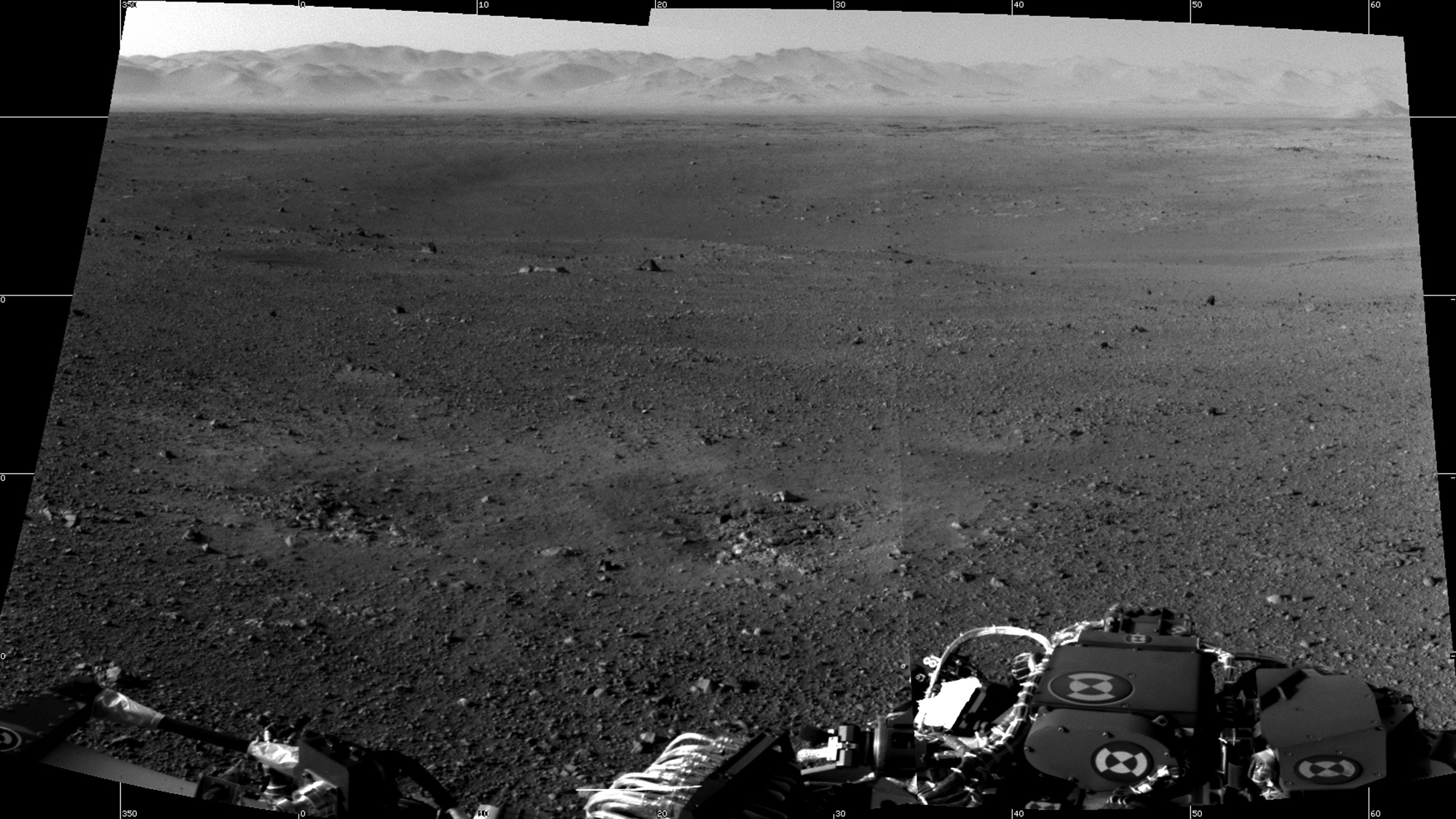

Curiosity has spent over a decade within the Gale Crater, the Martian landmark wherein it landed in 2012. The 100-mile-wide crater was fashioned by an asteroid influence some 3.5 to three.8 billion years in the past. It was chosen as Curiosity’s touchdown web site as a result of of the various indications that it was as soon as a lake. The soil samples gathered by Curiosity from the crater have a number of distinctive options: they include silica, and are wealthy in iron however poor in aluminum.

On Earth, this kind of soil is fashioned by “serpentinization”, a geological course of that ends in the conversion of numerous minerals into serpentinite. Crucially, this course of requires liquid water, and as such, the presence of materials with an analogous composition within the Gale Crater supplies additional proof that the crater was as soon as stuffed with water.

The different key attribute of the Martian samples is that they’re largely “x-ray amorphous,” which implies that they lack a repeating crystal construction that may be probed by x-ray diffraction. The amorphous nature of the samples got here as a shock to scientists, largely as a result of amorphous materials is mostly seen as solely “metastable”—because the study notes, it’s “susceptible to conversion to more thermodynamically stable and more crystalline mineral phases.”

Why this hasn’t occurred in Gale Crater stays unclear, however one concept is that the conversion course of is held again by “kinetically limiting conditions such as colder temperatures.” If that is the case, it suggests that Mars has at all times been a chilly place.

Given their incapability to study the Martian soil straight, the study’s authors did the subsequent neatest thing: they discovered comparable samples on Earth and studied the properties of these samples as an alternative. They searched a number of places with comparable soil compositions: two websites in California’s Klamath Mountains, one in western Nevada, and one in Gros Morne National Park, positioned on the Canadian island of Newfoundland.

Importantly, the samples from Newfoundland had been x-ray amorphous, whereas these from California and Nevada weren’t. This suggests that the chilly Canadian local weather has been essential in preserving the dearth of crystalline construction—and helps the speculation that one thing comparable occurred on Mars: “The presence of abundant [iron]-rich amorphous material at Gale Crater is consistent with cool and wet conditions during their formation, followed by cold and dry conditions promoting their persistence.”

“This shows that you need the water there in order to form these materials,” says Anthony Feldman, a soil scientist and geomorphologist now at DRI who co-authored the study. “But it needs to be cold, near-freezing mean annual temperature conditions in order to preserve the amorphous material in the soils.”

The study supplies a captivating perception into how scientists can infer details about an surroundings’s distant previous from its geological report. It additionally suggests that even within the long-past days when liquid water flowed on its chilly, distant floor, the Martian surroundings wasn’t particularly hospitable.