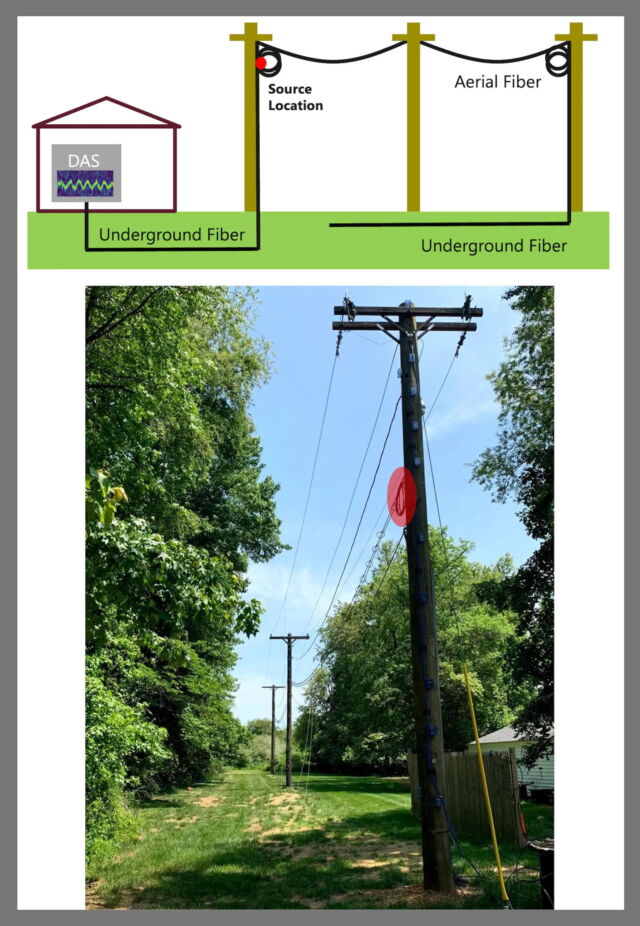

One of the world’s most peculiar take a look at beds stretches above Princeton, New Jersey. It’s a fiber optic cable strung between three utility poles that then runs underground earlier than feeding into an “interrogator.” This machine fires a laser by the cable and analyzes the sunshine that bounces again. It can choose up tiny perturbations in that gentle triggered by seismic exercise and even loud sounds, like from a passing ambulance. It’s a newfangled approach often called distributed acoustic sensing, or DAS.

Because DAS can monitor seismicity, different scientists are more and more utilizing it to observe earthquakes and volcanic exercise. (A buried system is so delicate, the truth is, that it can detect individuals strolling and driving above.) But the scientists in Princeton simply stumbled upon a slightly … noisier use of the expertise. In the spring of 2021, Sarper Ozharar—a physicist at NEC Laboratories, which operates the Princeton take a look at mattress—seen a wierd sign within the DAS knowledge. “We realized there were some weird things happening,” says Ozharar. “Something that shouldn’t be there. There was a distinct frequency buzzing everywhere.”

The group suspected the “something” wasn’t a rumbling volcano—not in New Jersey—however the cacophony of the enormous swarm of cicadas that had simply emerged from underground, a inhabitants often called Brood X. A colleague urged reaching out to Jessica Ware, an entomologist and cicada knowledgeable on the American Museum of Natural History, to substantiate it. “I had been observing the cicadas and had gone around Princeton because we were collecting them for biological samples,” says Ware. “So when Sarper and the team showed that you could actually hear the volume of the cicadas, and it kind of matched their patterns, I was really excited.”

Add bugs to the rapidly rising listing of issues DAS can spy on. Thanks to some specialised anatomy, cicadas are the loudest bugs on the planet, however all kinds of different six-legged species make lots of noise, like crickets and grasshoppers. With fiber optic cables, entomologists might need stumbled upon a strong new approach to cheaply and always eavesdrop on species—from afar. “Part of the challenge that we face in a time when there’s insect decline is that we still need to collect data about what population sizes are, and what insects are where,” says Ware. “Once we are able to familiarize ourselves with what’s possible with this type of remote sensing, I think we can be really creative.”

DAS is all about vibrations, whether or not they be the sounds of a singing brood of cicadas or the shifting of a geologic fault. Fiber optic cables transmit info, like high-speed Internet, by firing pulses of gentle. Scientists can use an interrogator machine to shine a laser down a cable after which analyze the tiny quantities of gentle that bounce again to the supply. Because the pace of gentle is a identified fixed, they’ll pinpoint the place alongside the cable a given disturbance occurs: If one thing jostles the cable 100 toes down, the sunshine will take barely longer to return to the interrogator than one thing that occurs at 50 toes. “Every 1 meter of fiber, more or less, we can turn it into a kind of microphone,” says Ozharar.

Journal of Insect Science/Entomological Society of America

Ozharar’s group targeted on a loop of the cable atop one of the utility poles, which you’ll see within the picture above. (The loop is highlighted in pink.) “If the fiber is in a linear shape, a sound interacts with the fiber just once and then keeps traveling,” says Ozharar. “But if you have a coil, the same signal travels multiple times through the fiber.” That makes the system far more delicate, like recording a live performance with a number of microphones, as a substitute of one fan within the crowd bootlegging it with their smartphone.

When Brood X emerged within the spring of 2021, Ozharar’s DAS system was by chance listening in. This form of “periodical cicada” develops underground and emerges each 13 or 17 years to mate, relying on the species. “Because of perhaps climate change—although we’re not exactly sure the reason—there have been stragglers, so populations that have come out early and populations that have come out later than what they’re metabolically timed to do,” says Ware. “Having a way to over time monitor those can be really helpful.”

Male cicadas have an organ, referred to as the tymbal, that vibrates like a drum to supply that unmistakable music. Each species has its personal variation on the music, permitting the appropriate women and men to search out one another. There’s additional info embedded in that sound, too: Males are inclined to name throughout the hottest time of day, which is energetically costly. That permits females to evaluate the standard of their mates—they need to select the fittest males so they’ll move primo genes to their offspring.

Hence all of the noise. DAS can pay attention from the very starting of the emergence by the height and into the decline because the mass mating ritual wanes. The quantity of noise is a strong indicator of the quantity of cicadas, so entomologists can work out the inhabitants measurement of the brood. They may even see the impact of temperature: When it’s hotter, it’s harder for the male cicadas to sing. “You can see that as you go across the five days from which we have monitoring data, that when it’s slightly colder temperatures they have slightly different frequencies in hertz of the calling,” says Ware.

Fiber optic cables are already all over, simply ready for scientists to faucet into them. They are plentiful in cities, of course, however additionally they run between them, which might be useful for entomologists who need to monitor bugs in additional rural areas. “We use them just to transmit the data—zeros and ones—but we can do much more,” says Ozharar. “That’s why fiber sensing will become more and more important, and more widely used, in the near future.”

Not that anybody’s suggesting DAS will exchange different methods of monitoring bugs—fiber optics are widespread, however they’re not in every single place. Instead, DAS may complement different strategies. A discipline referred to as bioacoustics already makes use of microphones to pay attention for species in distant areas, typically assisted by AI to parse the information. This methodology may assist verify the information coming from the fiber optics. Scientists are additionally experimenting with “environmental DNA,” or eDNA, for example utilizing air high quality stations to collect the organic materials floating in a given space. And entomologists like Ware nonetheless want to gather specimens from the sector to bodily look at the well being of particular person animals.

“What seems really cool about this new technology is that you have this single cable that can cover potentially many kilometers, and all of the information is getting recorded by a single device,” says Elliott Smeds, an entomologist and analysis affiliate on the California Academy of Sciences, who wasn’t concerned within the analysis. “Especially now that insects are declining, we’re realizing that we don’t even know what the baseline is for a lot of these species, to keep track of how they’re doing. The biggest obstacle is having enough boots on the ground to be collecting this kind of data.”

The trick shall be adapting DAS to observe species that aren’t the loudest bugs on Earth. “In this case, it was very clear these were cicadas, because there were—without exaggeration—millions of them that suddenly descended,” says Ware. “But in most cases, the populations are much smaller for each species. Knowing whether or not we can actually distinguish among insects will be an interesting question.”

This story initially appeared on wired.com.