NASA/JPL/Cal Tech

March 17, 2022, was a tough day for Jorge Vago. A planetary physicist, Vago heads science for half of the European Space Agency’s ExoMars program. His staff was mere months from launching Europe’s first Mars rover—a aim they’d been working towards for almost twenty years. But on that day, ESA suspended ties with Russia’s area company over the invasion of Ukraine. The launch had been deliberate for Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome, which is leased to Russia.

“They told us we had to call the whole thing off,” Vago says. “We were all grieving.”

It was a painful setback for the beleaguered Rosalind Franklin rover, initially permitted in 2005. Budget woes, companion switches, technical points and the COVID-19 pandemic had all, in flip, prompted earlier delays. And now, a warfare. “I’ve spent most of my career trying to get this thing off the ground,” Vago says. Complicating issues additional, the mission included a Russian-made lander and devices, which the member states of ESA would wish funding to interchange. They thought of many choices, together with merely placing the unused rover in a museum. But then, in November, got here a lifeline, when European analysis ministers pledged 360 million euros to cowl mission bills, together with changing Russian parts.

When the rover lastly does, hopefully, blast off in 2028, it should carry a collection of superior devices—however one particularly could make an enormous scientific influence. Designed to investigate any carbon-containing materials discovered beneath Mars’s floor, the rover’s next-generation mass spectrometer is the linchpin of a method to lastly reply essentially the most burning query in regards to the Red Planet: Is there proof of previous or current life?

“There are a lot of different ways that you can search for life,” says analytical chemist Marshall Seaton, a NASA postdoctoral program fellow on the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and coauthor of a paper on planetary evaluation within the Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. Perhaps the obvious and direct route is just on the lookout for fossilized microbes. But nonliving chemistry can create deceptively lifelike buildings. Instead, the mass spectrometer will assist scientists search for molecular patterns that are unlikely to be fashioned within the absence of dwelling biology.

Hunting for the patterns of life, as an alternative of buildings or particular molecules, has an additional benefit in an extraterrestrial atmosphere, Seaton says. “It allows us to not only look for life as we know it, but for life as we don’t know it.”

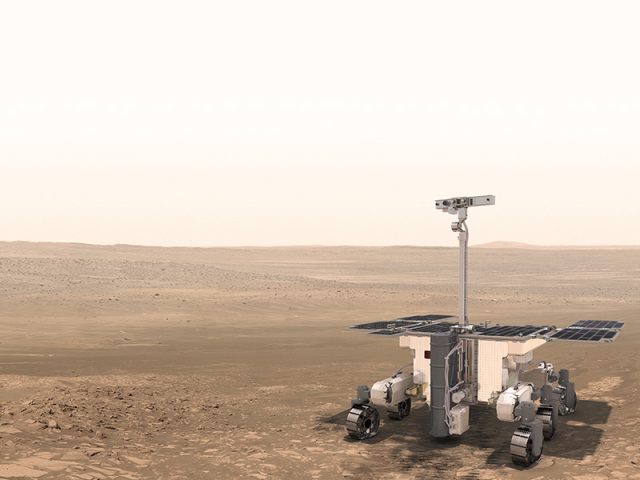

ESA/ATG MediaLab

Packing for Mars

At NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center exterior Washington, DC, planetary scientist William Brinckerhoff reveals off a prototype of the rover’s mass spectrometer, referred to as the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer, or MOMA. Roughly the scale of a carry-on suitcase, the instrument is a labyrinth of wires and steel. “It’s really a workhorse,” Brinkerhoff says as his colleague, planetary scientist Xiang Li, adjusts screws on the prototype earlier than demonstrating a carousel that holds samples.

This working prototype is used to investigate natural molecules in Mars-like soils on Earth. And as soon as the true MOMA will get to Mars, roughly in 2030, Brinckerhoff and his colleagues will use the prototype—in addition to a pristine copy stored in a Mars-like atmosphere at NASA — to check tweaks to experimental protocols, troubleshoot points that come up throughout the mission and facilitate interpretation of Mars knowledge.

This newest mass spectrometer can hint its roots again almost 50 years, to the primary mission that studied Martian soil. For the dual 1976 Viking landers, engineers miniaturized room-size mass spectrometers to roughly the footprint of at this time’s desktop printers. The devices have been additionally on board the 2008 Phoenix lander, the 2012 Curiosity rover and later Mars orbiters from China, India, and the US.

Anyone visiting Brinckerhoff’s prototype should first move a show case with a dismantled copy of the Viking instrument on mortgage from the Smithsonian Institution. “This is like a national treasure,” Brinckerhoff says, enthusiastically mentioning parts.

Mass spectrometers are indispensable instruments that are used for analytical chemistry in laboratories and different amenities worldwide. TSA brokers use them to check baggage for explosives on the airport. EPA scientists use them to check consuming water for contaminants. And drugmakers use them to find out chemical buildings of potential new medicines.

Many sorts of mass spectrometers exist, however every “is a three-part instrument,” explains Devin Swiner, an analytical chemist on the pharmaceutical firm Merck. First, the instrument vaporizes molecules into the fuel part, and in addition provides them {an electrical} cost. These charged, or ionized, fuel molecules can then be manipulated with electrical or magnetic fields in order that they’ll transfer by means of the instrument.

Second, the instrument types ions by a measurement that scientists can relate to molecular weight, to allow them to decide the quantity and kind of atoms a molecule comprises. Third, the instrument information all of the “weights” in a pattern together with their relative abundance.

With MOMA aboard, the Rosalind Franklin rover will land at a Martian web site that roughly 4 billion years in the past possible had water, a vital ingredient for historical life. The rover’s cameras and different devices will assist to pick samples and supply context about their atmosphere. A drill will retrieve historical samples from as deep as two meters. Scientists hypothesize that’s far sufficient, Vago says, to be shielded from cosmic radiation on Mars that breaks up molecules “like a million little knives.”

Space-bound mass spectrometers have to be rugged and light-weight. A mass spectrometer with MOMA’s capabilities would usually occupy a number of workbenches, but it surely’s been shrunk considerably. “To be able to take something that can be as big as a room to the size of like a toaster or a small suitcase and send it into space is a very huge deal,” Swiner says.